CDTFC’s Community Engagement Coordinator, Theresa Zubretsky, wrote a commentary piece published in the Albany Times Union today focusing on the disproportionate impact of menthol-flavored tobacco use on African Americans.

Read her commentary piece below.

Menthol-flavored tobacco is killing African Americans

Black History Month highlights previously unsung contributions of African Americans to our nation’s success. In tobacco control, we have our own unsung heroes, African American men and women battling tirelessly to end the death and disease caused by the tobacco industry’s relentless and targeted marketing of menthol cigarettes to the Black community.

These champions include Dr. Phillip Gardiner and Carol McGruder, co-chairs of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council. Their advocacy for policies to save Black lives led the way for a bipartisan group of 23 attorneys general to recently appeal to the FDA to ban the sale of menthol-flavored tobacco products.

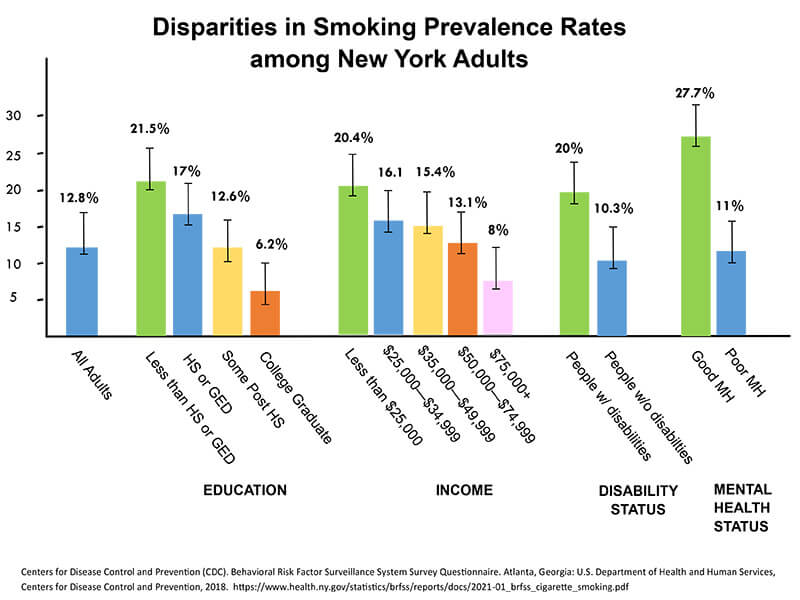

The disproportionate impact of tobacco use on African Americans is indisputable. Tobacco use contributes to the three leading causes of death among African Americans: heart disease, cancer and stroke. Blacks smoke fewer cigarettes on average and start smoking later than whites, yet are more likely to die of tobacco-related diseases. A significant contributor to these health disparities is menthol: Nearly 90 percent of African American smokers smoke menthol cigarettes, compared with 29 percent of white smokers.

A 2013 U.S. Food and Drug Administration report shows that the cooling and anesthetic effect of menthol allows smokers to inhale more deeply and hold the smoke in the lungs longer. As a result, menthol smokers show higher levels of nicotine addiction and decreased success quitting than non-menthol smokers, leading the NAACP to recommend that the FDA ban menthol in cigarettes.

It is no accident that African Americans disproportionately smoke menthol cigarettes and suffer and die more than whites from tobacco-related disease. Since the 1950s, the tobacco industry purposefully strategized to increase tobacco sales to the African American community. As detailed in a 1998 surgeon general’s report, the industry endeavored to curry favor among African American leaders and organizations while simultaneously intensifying efforts to increase menthol product appeal to the African American community.

The tobacco industry was one of the first to hire Black employees into top spots. They advertised in cash-strapped African American publications and provided funding to organizations including the Urban League, NAACP, and the Congressional Black Caucus. They provided scholarships and internships to aspiring Black students and sponsored events such as the Kool Jazz Festival and the Jackie Robinson Foundation Awards Dinner. In a particularly cynical move, Philip Morris saluted Nelson Mandela’s release from prison during Black History Month in 1990 to promote its $60 million Bill of Rights campaign, a campaign specifically intended to strengthen its self-interested notion of “smokers’ rights.”

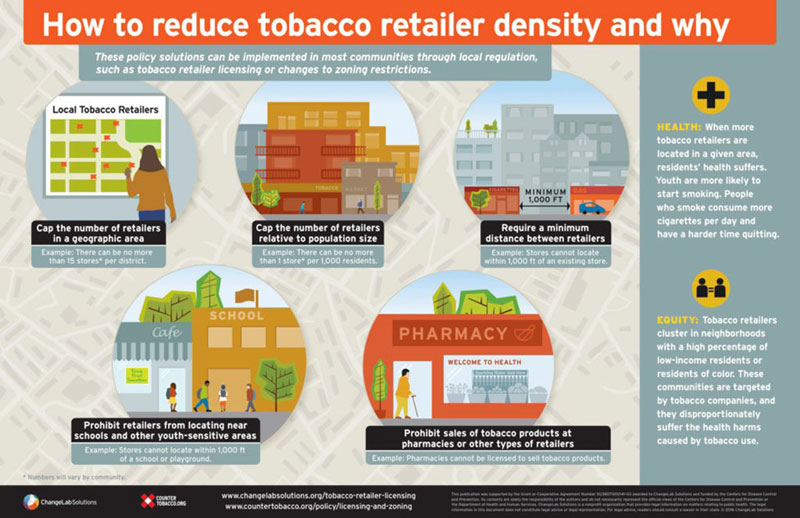

The point of all this strategic “philanthropy” was to insulate the industry from resistance to their aggressive peddling of menthol cigarettes to the African American community. And it worked. In 1953, only 5 percent of African American smokers used menthol; today, nearly 9 in 10 Black smokers do. Evidence of the tobacco industry’s continued efforts can be found locally: Predominantly Black neighborhoods have more tobacco retailers per capita, more ads, more menthol, and higher smoking rates.

The consequence of the tobacco industry’s decades-long campaign is that tobacco-related diseases kill more African Americans each year than AIDS, car crashes, murder, alcohol and other drug abuse combined.

COVID-19 has brought into even sharper focus the racial and ethnic health disparities that persist in our communities, disparities rooted in institutional racism. The tobacco industry capitalized on institutional racism and intensified these disparities by treating Black lives as dispensable in pursuit of profits.

Nearly 33,000 Black men and women have lost their lives to COVID-19. Even more die annually from tobacco-related chronic illnesses. It has never been more urgent to heed the calls from our African American tobacco control heroes. It is long past time to end the sale of menthol-flavored tobacco products.

To the left is a typical tobacco product display. If you don’t use tobacco, you may not even notice, but kids do. Kids see. Kids notice. Kids remember. In fact, kids are more than twice as likely as adults to notice and remember retail tobacco marketing.

To the left is a typical tobacco product display. If you don’t use tobacco, you may not even notice, but kids do. Kids see. Kids notice. Kids remember. In fact, kids are more than twice as likely as adults to notice and remember retail tobacco marketing.