Today is #SeenEnoughTobaccoDay, which highlights the need for communities to protect children from the billions of dollars of tobacco marketing in places where kids can see it. The 13th was selected to underscore the alarming fact that the average age of a new smoker in New York is 13 years old.

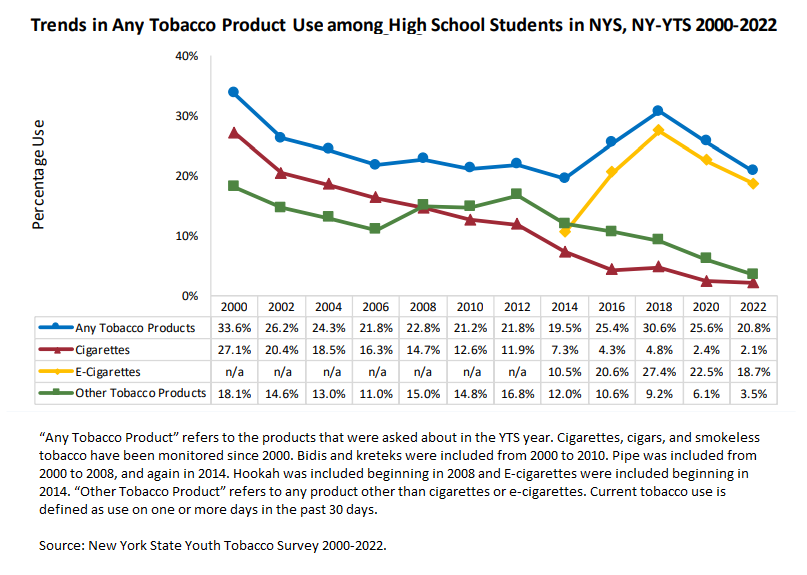

While New York State’s recent ban on flavored e-cigarettes is a significant step toward reducing youth tobacco use, other flavored tobacco products, such as little cigars, chew and menthol cigarettes that are still on the market present an obstacle to decreasing tobacco use among young people and minority populations.

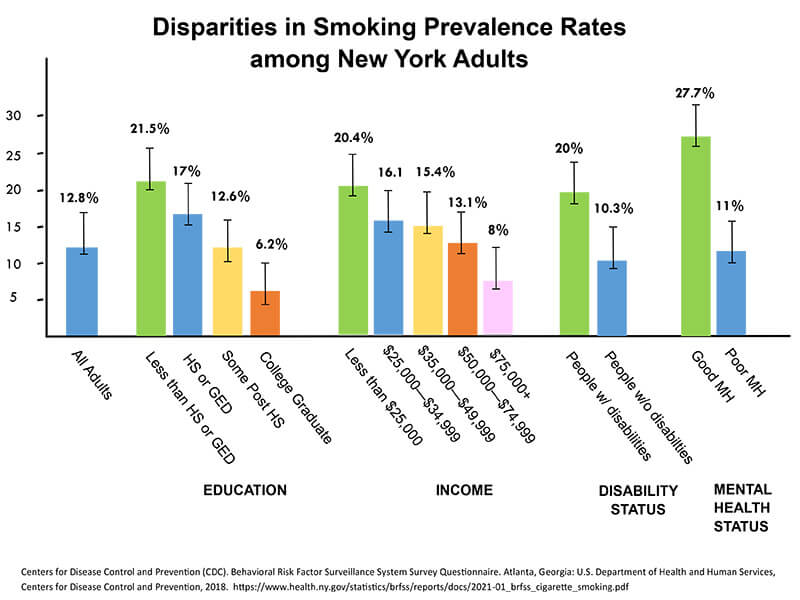

Menthol use among Black communities is a direct result of the tobacco industry’s marketing practices and product manipulation. Tobacco companies add menthol to make cigarettes seem less harsh and more appealing to new smokers and young people. Essentially, menthol in tobacco products, makes it easier to start and harder to quit.

Research indicates that:

- Young people and African Americans are more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes than other groups.[1],[2]

- More than half (54%) of youth who smoke use menthol cigarettes.[3]

- Over 7 out of 10 African American youth ages 12-17 years who smoke use menthol cigarettes.[4]

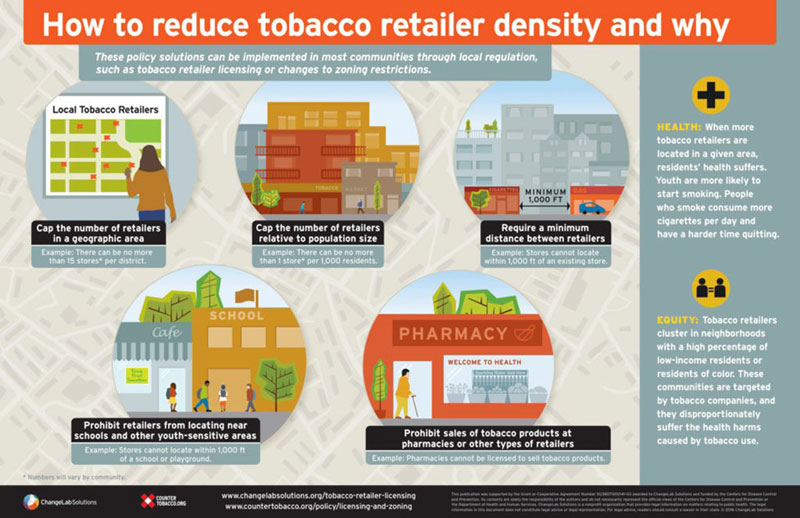

Here in the Capital District, Reality Check members have provided a vital youth perspective on the impact of tobacco marketing on young people on issues ranging from the mixed message of selling tobacco in pharmacies, the importance of raising the tobacco sale age to 21 and the youth appeal of flavored tobacco products, including menthol. Their education contributed to local and state adoption of Tobacco-Free Pharmacies, Tobacco 21 and a statewide ban on the sale of flavored e-cigarettes.

[1] Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations pdf icon[PDF–15.3 MB]external icon. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2011.

[2] Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes pdf icon[PDF–1.6 MB]external icon. 2013.

[3] Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004-2014external icon. Tob Control. 2016;25:ii14-ii20. Doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053329.

[4] Ibid. Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004-2014external icon. Tob Control. 2016;25:ii14-ii20. Doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053329.

To the left is a typical tobacco product display. If you don’t use tobacco, you may not even notice, but kids do. Kids see. Kids notice. Kids remember. In fact, kids are more than twice as likely as adults to notice and remember retail tobacco marketing.

To the left is a typical tobacco product display. If you don’t use tobacco, you may not even notice, but kids do. Kids see. Kids notice. Kids remember. In fact, kids are more than twice as likely as adults to notice and remember retail tobacco marketing.